1. INTRODUCTION

There has been intense scrutiny for lifestyle investors’ role in vineyard ownership and demand. Vineyard lifestyle investors can be defined as hobbyists who enjoy living in a vineyard environment but are less interested in large scale farming or production activities. For example, Morton and Podolny (2002) hypothesize that vineyard owners, similar to the ownerships in professional sports teams, newspapers, and art galleries, enjoy wine product or wine production process as their non-financial return. Furthermore, Morton and Podolny question the motivation behind vineyard ownership in California by saying: “Love or Money?” Also, Brook (1999) states that “Owning a wine estate in California, especially in Napa Valley, is a ‘lifestyle choice’ rather than, as in Europe, the perpetuation of a family tradition.” Similarly, according to Thomas (2011) “… most wealthy vineyard owners are ‘lifestyle’ buyers seeking a holiday house with a few hectares of vines, although there are those who take it more seriously.” Rand (2008) exposes the dual nature of a lifestyle vineyard investor goal by saying: “Do you want a lifestyle, or do you want a profitable business?” Also, Dominici et al (2019) investigate small-medium and family-run Tuscan winery owners and find that “Passion, independence and a desire to live close to nature are predominant compared to pecuniary motivations, such as profit maximization.” In addition, Sugand (2014), Dawson (2012), Morton and Podolny (2002), and Charters et al. (2016) discuss the dual nature of a vineyard owner’s goals for lifestyle investors.

Therefore, it is possible to describe a lifestyle vineyard investor goals as:

- Maximize vineyard owner’s utility from vineyard living and lifestyle with family and friends, and

- Stay above break-even profit level that supports the owners’ lifestyle.

The second objective falls short of a typical firm’s goal expressed as “owners wealth maximization” or “profit maximization.” Therefore, the second goal, at best, suggests a level of earnings that sustains or supports the achievement of the first goal.

Similar to Brook (1999), Cotterill (2018), and Keohane (2018), Santos et al. (2022) also points to high land prices as a limiting factor in vineyard ownership especially for newcomers. Santos et al. claim that over time, the conglomerate firms’ vineyard ownership in the famous wine regions such as Napa, California, may increase, because high land prices are a barrier to entry. Thus, high land prices may constrain lifestyle investors’ ownership especially in large vineyards because it will require significant amounts of startup capital in addition to the large-scale farming activities.

In famous wine regions of the world, it can be hypothesized that lifestyle investors’ demand is likely to be skewed towards small vineyard ownership because of the lifestyle investors’ preferences and high land prices. Even though it is hard to know the exact cutoff point (if exists) in acres to define what a small vineyard is, less than 10 or 20 acres is thought to be small and attractive to most lifestyle investors.

In addition, there is extensive research beyond vineyard land that examines whether small parcel sizes have a premium or whether larger parcels receive a discount. For example, Ritter et al. (2020) analyze agricultural land price data from the German federal state of Saxony-Anhalt and find that, unlike other financial assets, land is traded in relatively illiquid markets with significant search and transaction costs. These market frictions contribute to a complex relationship between land price and parcel size, where price per unit of land is not independent of transaction size. Using semiparametric regression methods, the authors demonstrate that this relationship is nonlinear and influenced by multiple economic factors, including economies of scale, transaction costs, and financial constraints. Their findings suggest that smaller parcels can often have a higher price per hectare, although the effect varies depending on local conditions and buyer preferences.

The motivation of this paper is to investigate why smaller vineyards have higher appraised land values per acre in Napa, California. There are two hypotheses consistent with higher appraisal values for small vineyards: (1) There might be a preference of life-style investors to live in a small vineyard environment. (2) The economies of scale (or lack thereof) indicate that the larger the land, the cheaper it becomes per acre including vineyards. In addition, this paper explains the vineyard appraisal methodologies used by Napa County.

Further, a large section of this study entertains the role of life-style investors in small vineyard appraisal valuation because of the informal conversations with the assessor of Napa County. To our knowledge, this is the first research paper that uses appraisal land value to analyze lifestyle investors’ demand for small vineyards and its effects on the vineyard land appraisal values in Napa, California.

2. RESEARCH

2.1. Data and the Appraisal Method

The appraisal data for this paper is obtained from Napa County’s Assessor (Recorder and Clerk) in California for the 2017-2021 period.[1] The original data includes 170 vineyard properties. A positive grow value indicates that there are already mature vines on the property which is thought to be an attractive feature to lifestyle investors. In addition, two properties with less than 1 acre are excluded from the sample. As a result, 168 vineyard property data is used for this research.

Napa County assesses the vineyard base year values when there is a change in ownership or new construction. For example, Napa County assessed $3.5 billion value of vineyards (approximately) in 2021-2022 tax year out of the $45.6 billion total vineyard assessment potential.[2]

Napa County assessor uses the following formula for the vineyard appraisal:

Total Vineyard Value = Land Value + Structure Value + Grow Value + Fixtures Value

Where, the land value uses “sales comparison method” and compares a specific vineyard with others in the same region using various units of measure such as the price of comparable vineyards per acre. Naturally, the assessor makes adjustments to the vineyard value by taking into account other factors such as location, climate, soil characteristics, water availability and distribution systems, and grape prices. If the vines in a vineyard are sufficiently mature and have potential to produce grapes, the assessor can also use the “income approach” by forecasting future cash flows. The income method takes into account the potential income that can be generated from the vineyard based on factors such as grape prices and production levels. Napa County does not use the cost method which takes into account the costs associated with establishing and maintaining a vineyard.

The structure value at a vineyard is appraised similarly to the appraisal of residential buildings. Further, the “grow” value of a vineyard refers to the value of the grapes as they grow and mature on the vine. In this case, factors such as the quality of the grapes, the yield per acre, and the market demand for the grapes is considered. Fixtures value adds to the overall value of a vineyard if it has trellis, sprinkler and drip irrigation systems.

According to Baxevanis (1992) the income approach provides better results for appraising vineyards because the future income of vines is incorporated. However, Baxevanis also agrees that factors such as the climate, access to water, location, soil quality should be considered for adjusting vineyard values.

This paper focuses on appraised land value per acre. Unfortunately, The Napa County data does not have the “planted acreage” data for the vineyards and that is one of the limitations of this study.

2.2. Analysis and Findings

There is no universally standardized system for classifying vineyard sizes, and classifications are often based on acreage or hectares. To avoid arbitrary cutoff points for vineyard sizes, the vineyards in this study are classified as follows: Small (1 to 10 acres), Broader Small (1 to 20 acres), Medium (10 to 40 acres), Broader Medium (10 to 50 acres), Large (50 to 100 acres), and Broader Large (40 to 100 acres).

The vineyard appraisal land value per acre is calculated by dividing the appraised total land value by the corresponding number of acres. Regressions are run for six groups: Small (1 to 10 acres), Broader Small (1 to 20 acres), Medium (10 to 40 acres), Broader Medium (10 to 50 acres), Large (50 to 100 acres), and Broader Large (40 to 100 acres). In these regressions, the appraised land value per acre is on the Y-axis as the dependent variable, and acres are on the X-axis as the independent variable.

Table 1 presents regression results for the appraised land value per acre as a function of total vineyard acreage across various size categories in Napa, California. The intercepts, significant at the 1% level, represent the estimated value per acre when only one acre is considered, effectively the initial price point for the smallest possible purchase in each category.

The results underscore a clear pattern: smaller vineyard parcels provide significantly higher land values per acre, and these values decline with increasing vineyard size.

For very small vineyards (1 to 10 acres), the appraised land value per acre begins at a steep $1,133,741.47, with a large and statistically significant decline of $114,467.31 per additional acre, reflecting strong economies of scale in this smallest range.

In the broader small category (1 to 20 acres), the starting value drops to $830,209.57, and the negative slope of -$44,663.89 per acre, statistically significant, confirms that the cost per acre declines as more land is acquired, though the effect is less dramatic than in the 1–10 acre range.

For medium-sized vineyards (10 to 40 acres), the intercept decreases further to $252,998.24, with a statistically significant but milder reduction in value per additional acre (-$3,103.21), indicating a continued but diminishing scale effect.

In the broader medium 10-to-50-acre group, the slope flattens to -$764.46, which is not statistically significant, suggesting that for this size range, the per-acre price stabilizes and scale economies taper off.

In the large 50-to-100-acre group, the intercept rises unexpectedly to $300,459.91, and the slope becomes notably negative again at $-3,030.60, statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that within this narrower range of large vineyards, additional acreage is still associated with lower per-acre values, perhaps due to location quality or plot subdivision patterns within that range.

The broader large vineyard category (40 to 100 acres) shows a dramatic drop in land value per acre, starting at only $71.07, with a minute but statistically significant negative slope (-$0.000091), essentially reflecting a flat price structure across very large parcels.

When considering all sizes combined (1 to 624 acres), the average entry cost is $336,047.79 per acre, and the overall trend remains statistically significant with a negative slope of $-1,330.71, reinforcing the general inverse relationship between vineyard size and land value per acre.

In summary, land value per acre in Napa vineyards tends to decline as vineyard size increases, with the strongest marginal declines seen in smaller plots. Beyond around 40–50 acres, the per-acre price levels off or drops only slightly, although specific subgroups (like 50–100 acres) may still experience meaningful discounts with additional acreage.

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the relationship between vineyard size and land value per acre for two vineyard size categories, small (1 to 10 acres) and medium (10 to 40 acres), in Napa, California, from 2017 to 2021. Both figures show downward-sloping trendlines, indicating an inverse relationship between acreage and appraised value per acre, though the rate and scale of decline differ markedly between the two categories.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between vineyard size (in acres) and land value per acre for small vineyards (1 to 10 acres) in Napa, California, from 2017 to 2021. Each dot represents an observed data point, and the solid line is the fitted linear regression trendline based on the equation:

Value per Acre = $1,133,741.47 - $114,467.31 × Acres.

The negative slope of the trendline reflects a clear inverse relationship: as the size of the vineyard increases, the appraised land value per acre decreases. This pattern supports the concept of diminishing marginal land value in small parcels, suggesting that buyers pay a premium for the first few acres, likely due to fixed costs or scarcity. The downward trend is statistically significant, consistent with the regression results shown in Table 1, and emphasizes that smaller parcels have higher per-acre prices in Napa’s premium vineyard market.

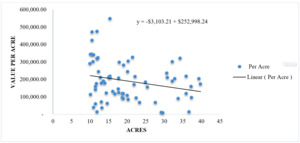

Figure 2 displays the relationship between vineyard size (in acres) and the appraised land value per acre for medium-sized vineyards (10 to 40 acres) in Napa, California, over the period 2017–2021. The data points represent individual vineyard observations, and the solid black line represents the linear regression trendline derived from the equation:

Value per Acre = $252,998.24 - $3,103.21 × Acres.

The negative slope of -$3,103.21 indicates that, on average, the land value per acre decreases slightly as vineyard size increases within this medium range. However, compared to smaller vineyards (as shown in Figure 1), the decline per additional acre is much less steep, reflecting diminishing returns to scale at a slower rate. This suggests that economies of scale are still present in medium-sized vineyards but are less pronounced than in smaller parcels. The spread of data points also indicates considerable variability in per-acre values, possibly reflecting differences in location, terrain, or vineyard quality.

Null hypothesis (The population mean land values per acre are equal for all three vineyard size groups.)

Alternative hypothesis : At least one differs (At least one group has a different population mean land value per acre.)

The null hypothesis assumes there is no significant difference in average land values per acre between the three size categories. Rejecting would suggest that vineyard size has a statistically significant effect on appraised land value per acre.

To test whether the differences in average appraised land value per acre are statistically significant across vineyard size categories, a one-way ANOVA was conducted for the small vineyards (1 to 10 acres), medium vineyards (10 to 40 acres) and broader large vineyards (40 to 100 acres)

Since the F-statistic (36.73) is substantially greater than the F-critical value (3.06), we reject the null hypothesis at 1% and 5% significance levels. This means there is a statistically significant difference in mean land value per acre among the three vineyard size categories.

Therefore, the following implications can be inferred from the results.

-

Small vineyards (1 to 10 acres) have the highest average appraised land value per acre ($632,598), more than three times higher than medium-sized parcels.

-

Medium vineyards (10 to 40 acres) average $190,645 per acre, while broader large vineyards (40 to 100 acres) are slightly lower at $145,683.

-

These results are consistent with earlier regression findings and support the idea that smaller vineyards have a premium per acre, likely due to their scarcity and appeal to lifestyle buyers. There is higher demand by the lifestyle investors in Napa for smaller vineyards. Napa County assessor primarily uses the “sale comparison method” which incorporates the comparable vineyard land prices in the region for the land value appraisals. Therefore, it is likely that the higher demand of the lifestyle investors drives up the land prices and subsequently appraisal values per acre.

-

The pattern is also consistent with economies of scale, where larger parcels tend to have lower per-acre costs. The economies of scale that come with bulk purchasing: more acres you buy, less expensive it gets. Herrick (2015) stresses on the economies of scale in vineyard management by suggesting that the cost of installing vines and trellis in large vineyards could be at a lower cost per acre than smaller vineyards." However, the lower cost per acre installation cost does not necessarily translate cheaper land per acre for medium to large vineyards.

The Napa data has limitations to gauge the “planted acreage” in the vineyards. Therefore, the data does not indicate whether the planted acreage size goes down or not with the medium to large vineyards. There is a possibility that larger the vineyards, smaller the planted acreage available. However, we do not have data to support this hypothesis.

Having cheaper land value for medium to large vineyards raises a question about arbitrage opportunities. For example, is it possible for an investor to buy 100 acres of vineyard land at lower prices per acre, divide this large vineyard into 10 equal sizes of small vineyards (with each having 10 acres) and sell them at higher prices? What are the costs and obstacles to this type of arbitrage? Does the cost of dividing the land, installing infrastructure, and obtaining necessary permits and approvals offset profit and arbitrage opportunities? Does data support the existence of a higher number of small vineyards over time perhaps converted from larger vineyards into smaller ones in the famous wine regions of the world? It should be noted that the discussion of arbitrage opportunities is included not as a central empirical claim, but rather as a theoretical implication of the observed price differentials. When small vineyards are valued at a premium per acre, it naturally raises the question of whether investors could capitalize on this difference by subdividing larger properties. Thus, this discussion is intended to illustrate the economic logic that follows from a market pattern in which pricing inefficiencies may exist.

Another discussion topic is about a statement by Herrick (2015): “With many of our vineyards developed by individuals without a background in agriculture, sometimes contracting out the job is the most efficient way to proceed.” If lifestyle investors’ main goal is to enjoy the utilities of vineyards, naturally contracting out vineyard management operations to other firms specializing in vineyard farming and viticulture can be an optimum choice. Does that mean if there are more firms providing vineyard farming and viticulture services in a wine region, it is an indication of more lifestyle investors living there?

The findings of this study are also consistent with the economies of scale argument. Economies of scale suggest that larger vineyards are more cost-efficient to operate. Larger vineyard parcels follow the principle of economies of scale because fixed costs (such as equipment, labor, infrastructure, and management) can be spread over more acres, reducing the average cost per unit of production. Additionally, larger operations often benefit from greater bargaining power with suppliers, more efficient use of machinery, and streamlined logistics. As a result, producing wine on a larger scale becomes more cost-effective, making bigger vineyards more attractive to commercial operators seeking to maximize profitability.

While the principle of economies of scale suggests that smaller vineyards are less cost-efficient to operate due to higher per-unit production costs, this does not conflict with the finding that smaller parcels have higher land values per acre. The regression analysis in this study focuses on land acquisition costs, not ongoing operational efficiency. The elevated per-acre values for smaller vineyards likely reflect market dynamics such as scarcity, prestige, and demand from non-commercial buyers like lifestyle investors, rather than cost-effectiveness. In this context, the observed pricing structure is entirely consistent with economies of scale: larger parcels appeal to commercial operators due to lower marginal costs, while smaller parcels have a premium due to their limited availability and appeal to a different segment of buyers.

3. CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS, AND STUDY LIMITATIONS

This paper investigates why small vineyards have higher per-acre appraised land values in Napa, California. While the findings do not offer definitive evidence that lifestyle investor demand is the primary driver, the analysis supports the hypothesis that such demand plays a significant role. Lifestyle investors are likely to prefer smaller vineyards because they are more manageable and still offer personal enjoyment through grape cultivation and wine production. In contrast, vineyards exceeding 10 or 20 acres may deter lifestyle buyers due to the time and expertise required for farm management.

Napa County’s use of the sales comparison method for appraisals suggests that higher market prices for small vineyards are driven by lifestyle demand influencing their appraised values. Statistical analysis using F-tests and t-tests confirms significant differences in both the means and variances of appraised land values per acre between small, medium, and large vineyard parcels. These results are more consistent with lifestyle-driven demand than with economies of scale.

Although economies of scale can explain some of the lower per-acre prices of larger vineyards, due to reduced infrastructure and operating costs per acre, this explanation is less compelling in premium wine regions like Napa, where professional scrutiny and non-economic motivations also affect land values.

This study also highlights a key distinction in investor motivation. Unlike typical firms that pursue profit maximization, lifestyle investors are often content with sustaining profitability above a break-even level in exchange for personal utility derived from vineyard ownership and associated experiences.

3.1. Study Limitations

This study uses appraisal data rather than actual market sales prices. The assessed values used for Napa County taxation purposes may not fully reflect current market conditions. Therefore, discrepancies between appraised and market values may stem from factors such as lifestyle investor premiums, zoning and environmental restrictions, and limitations in appraisal methodologies.

Another plausible explanation for why small vineyards are more expensive per acre is that they are often easier to finance and manage, and they are more attractive to individual or lifestyle buyers. These properties may change hands more frequently than larger vineyard holdings, driven by higher turnover among non-commercial owners. As a result, their assessed values may align more closely with current market prices, especially if recent sales data are used in valuation models.

In addition, one reason small vineyards may have higher prices per acre in Napa County is the influence of AVA premiumization. The American Viticultural Area (AVA) system is a federally recognized designation for wine grape-growing regions in the U.S. This system helps define regional identities in the wine industry and allows wineries to market their wines based on geographic origin. Consumers often associate certain AVAs with high-quality wines, resulting in higher prices. Additionally, small vineyards may be more desirable if they are located in high-demand sub-AVAs, have better-planted acreage, or include luxury real estate homes.

3.2. Recommendations for Future Research

Even though transaction costs, infrastructure investments, and regulatory hurdles are likely to prevent arbitrage opportunities between small and large vineyards due to price discrepancies per acre, future empirical research could explore the feasibility and prevalence of such arbitrage strategies, or track parcel subdivision over time in Napa and other wine regions. To better understand the motivations behind small vineyard purchases, future studies could employ survey methods targeting owners in Napa. Further research may also examine the role of third-party vineyard management services, particularly for lifestyle investors who may outsource farm operations while retaining ownership and enjoyment.

In addition, future research may explore the relationship between AVAs and high-quality wines to determine whether AVA premiumization contributes to the per-acre price discrepancies between small and large vineyards.

We thank John Tuteur (Assessor, Recorder, and County Clerk) of Napa County, California for generously providing the data.

See Napa County Website at https://www.countyofnapa.org/1072/Valuing-Vineyards.